A nut was a nutrition-unit, creation of the Ministry of Synthetic Food.

–Anthony Burgess, The Wanting Seed (1962)

If you should ever plan a trip to utopia, you’ll want the pack your loosest clothes. The food there is fantastic — and there’s plenty of it. The land of Cockaigne, the subject of legend in Europe going back to the Middle Ages, greets visitors with streets paved with buttery pastries in place of cobblestones. In the New World, the fabled city of El Dorado, said to lie hidden in the jungles of Colombia, offers paradise for gourmands and treasure hunters alike. There fountains, if they don’t spray jets of rose water, issue great gouts of sugarcane liquor. Further north, the Big Rock Candy Mountain, which fueled the dreams of hobos throughout a depression-plagued United States, is home to lemonade springs and hens that lay hard-boiled eggs.

Travel to dystopia, on the other hand, and you’ll want to pack a lunch. There is local cuisine, of a kind. But it will make you question, whether, in a place in which life has reached its greatest potential for awfulness, the food of the place hasn’t, as well.

The answer to that question is: It depends. Whereas overwhelming abundance in utopias moots the issue of feeding the masses, in dystopias it’s an abiding concern. Food is neither cheap nor free on a planet gone pear-shaped, and it’s never plentiful — not that anyone would wish it to be. As any survey of dystopian fiction shows, food in these dreary domains is, at best, wholesome, if synthetic and tough to get. At worst, it’s synthetic, tough to get, and repulsive, to boot.

For examples of the latter, we can start with Canadian writer Margaret Atwood’s 2003 novel, Oryx and Crake. In its post-apocalyptic world, people kick off their day with Choco-Nutrino, a breakfast cereal made entirely of synthetic ingredients. It came to market in response to a global collapse of the cacao crop. Lunch offers a few options: SoyOBoy burgers, which are as flavorless as they are meatless, and ChickieNobs. The latter are nuggets made with the meat of chicken genetically engineered to be an “animal protein tuber.” The altered fowl exists as a kind of “chicken hookworm,” having only a torso and a gaping mouth for receiving feed. Short on “chickie” and long on “nob,” its meat has a “bland tofu like consistency” and an “inoffensive flavor.” Though inoffensive, which is perhaps the most you could ask of it, it’s not especially healthy. Those folks for whom ChickieNobs are a staple come to have a complexion that looks like “regurgitated pizza.”

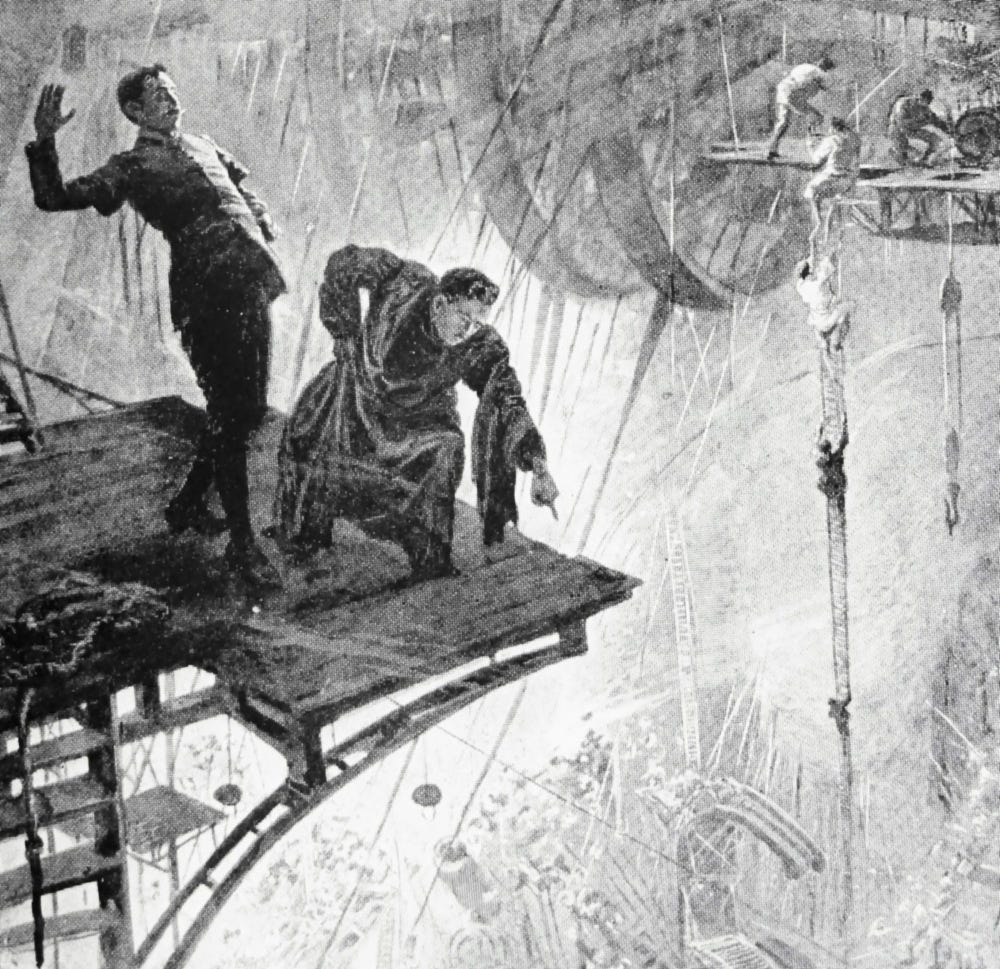

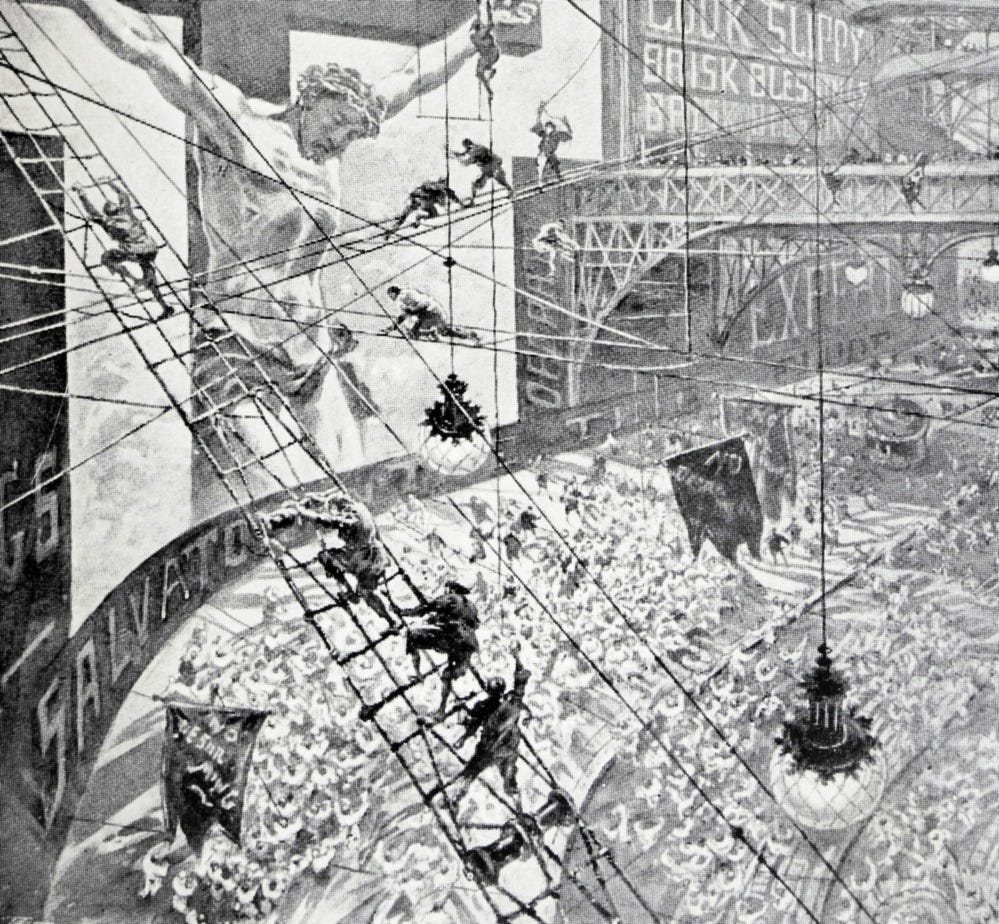

Yet maybe Atwood’s ChickieNobs would prove more tempting up against the fare in H.G. Wells’s 1899 novel of a dismal future, When the Sleeper Wakes. It’s set in London at the dawn of the 22nd century. The city and the rest of Britain is ruled by a plutocratic elite that forces the 99 percent of inferior souls to subsist on “pink fluid with a greenish fluorescence and a meaty taste.” Helping the fluid to go down easier is “chemical wine,” which blunts tastebuds and hope with equal effectiveness.

Pink equals “blah” in 1984, as well. It’s the hue of the “cubes of spongey … stuff” passed off as stew beef by the central authority of George Orwell’s 1949 novel. The pink, spongey stew usually came served with bread, coffee, and cheese of a uniform gray. So joyless is the “filthy-tasting” platter that it leads the main character, Winston Smith, to wonder, “Had food always been like this?”

The narrator of We, the 1921 novel by Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, knows that food hadn’t always. Known only as D-503, he informs readers that in his totalitarian world “petroleum food” ended mass hunger. Invented, readers learn, in the “thirty-fifth year before the foundation of the United State,” petroleum food needs to be chewed fifty times before an eater could swallow it. Those fifty meeting of molars presumably deliver little in the way of savor, for D-503 says nothing of its taste. Any idea that readers gather as to taste comes only by way of comparison. D-503 speaks of “primitive peasants” who, prior to the founding of the United State, loved bread and other non-petroleum-based foods. Unfortunately, by the time of D-503’s telling bread had fallen into oblivion, it’s very chemical composition become a mystery in the wake of petroleum food’s triumph.

Leave it to English writer Aldous Huxley to add a twist to dystopian fare. His 1932 novel Brave New World features food that isn’t so much dispiriting necessarily as blandly wholesome: “pan-glandular biscuits,” accompanied by carotene sandwiches, pâté of vitamin A, and beef-surrogates. To wash it all down there are caffeine solutions for adults; for children, “pasteurized external secretions.”

The forgoing remarks are not to say that appealing food is absent from dystopia. It does appear, albeit as means rather than an end — the means of awakening memories of a time before dystopia’s consolidation, a time in which lives were lived more freely and rewardingly. If it happens that characters have no such memories, then pleasant fare awakens them to a desire for a life in which such memories may be made. In either case, a satisfying meal stirs dystopian diners to rebellion, if it is not itself already a rebellious act.

Refection and rebellion meet in the person of Guy Montag, the central character in American writer Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel, Fahrenheit 451. Readers join Montag as he plies his trade of “fireman” tasked by the novel’s authoritarian powers to raise books to the titular temperature, thereby razing knowledge to the metaphorical ground. Montag tires of this pursuit, however, and the anti-intellectual environment it supports. He takes up with a band of intellectuals eking out an outlaw existence in the wilderness. One of the first meals Montag eats with them is bacon fried over a campfire, the aroma of which fills the air. The realness of it breathes freshness into life spent consuming mass entertainment “leveled down to a sort of paste pudding norm.” At another point he delights in the heady aromas of the natural world, savoring the scent of something in the air that smells like a cut potato, and something “like pickles from a bottle and a smell like parsley on the table at home … a faint yellow odor like mustard from a jar.” After plucking a weed, he notes that “his fingers smelled of licorice.” Such earthy scents are connected to the essence of life, the simple things that constitute the majestic whole.

Whereas a savory or dainty speaks to Guy Montag of the part and the whole, to Winston Smith it speaks of present and past. Given a chocolate bar by his lover Julia, he finds himself transported to his youth. Julia’s gift is the real McCoy and, for that reason, unusual — dark and shiny, wrapped in silver — rather than the “dull-brown crumbly” ersatz fobbed off by Big Brother. The first whiff of the confection stirs up a memory of the old world, a memory which “he could not pin down, but which was powerful and troubling.” Julia later brings him sugar. Winston does not recognize the “heavy, sandlike stuff” at first. Yet he knows by sight the “proper white bread” and jam she unwraps, as well as the real coffee she serves with real milk. The“rich, hot smell” of the coffee seems “like an emanation from his early childhood.”

Our hero of Huxley’s Brave New World, John Savage, takes a decidedly more vigorous approach to tasting of the past. A future London of runaway scientism sends him fleeing to the wilds beyond. There he vows to live on waterfowl and small game. To supplement the spoils of the hunt he adds wheat flour and homegrown produce. He draws the line at the synthetic and recovered-ingredient offerings of the metropolis, however. No “cotton-waste flour substitute” shall pass his lips again. (John Savage does at one point break his vow by buying some pan-glandular biscuits and vitaminized beef-surrogate, a lapse for which he later curses himself.)

Tasty, simple food, then, offers an antidote to the deadening effect of dystopia. It awakens memories and long-dormant senses. And it reconnects us with our innermost selves and the natural world. The dystopian impulse is to reduce the many worthwhile features of human existence, be they joyful or heart-rending, to a chirping monotony, be it drab or lurid, of material progress. In dystopia, the delightful, organic panoply of life lived freely is at first tainted, and later replaced, by a monolithic, synthetic order fueled by fear.

We can learn much from these novels. Between pandemic, war, inflation, corporate monopolies, a febrile climate, climbing rents and mortgages, and technologies that snoop and scold, it may be that dystopia’s hour has come round at last. We have all the more reason, then, to cherish the simple, human pleasures that remain to us — and to brace for worse things to come.

Try this simple recipe for old fashioned roast turkey from The Beloit Cook Book (1914). Guaranteed free of nobs, it’s a dish that can hearten and delight.

Old-Fashioned Roast Turkey

Wash thoroughly on the outside with warm water, soap and brush, rinse and dry. For the stuffing, use 2 baker’s loaves of 1 day old bread, crumble very fine dry, season highly with pepper and salt and molten with 1 cup melted butter. Stuff the turkey, sew up opening, truss legs and wings tightly, cover legs with oiled paper to prevent dryness. Rub over with salt and butter, dredge lightly with flour and put in hot oven for ½ hour and 1 ½ pints water in pan. Then cover, not closely, and bake moderately until tender. Then remove cover and brown.

Oyster Dressing for Turkey: One quart oysters, 1 pound oyster crackers, ½ pound butter. Salt and pepper.

If you’d like to help the Kitchen keep cookin’, please consider picking up a copy of my book, which you may find on one of the sites listed here.

Fascinating journey! One thing that struck me is how reflective dystopian literature is of the joyless, industrial, nutritionism so prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One in particular struck me: "cotton waste flour substitute" was actually a real, quasi-food: cottonseed. Cottonseed oil was (and perhaps still is?) the main ingredient in Crisco (whose predecessor was the less-appetizingly-named Cottolene, made entirely from cottonseed oil) and other "vegetable oil" concoctions of the industrial food system. Cottonseed is a by-product of the cotton industry, and cottonseed meal is still a popular ingredient in cattle feed, due to its high fat and protein content. It has since been overtaken by soy, in both the "vegetable" oil and cattle feed categories, but you still find it from time to time listed on ingredients lists - usually in foods from other countries who don't feel the need to obscure ingredients.

Anyway - it just struck me enough to comment about it!