Berrying with Thoreau

Let the amelioration in our laws of property proceed from the concession of the rich, not from the grasping of the poor … Let us understand that the equitable rule is, that no one should take more than his share, let him be ever so rich.–Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Man the Reformer” (1841)

Of those writers who flung themselves against Mt. Monadnock’s steep, rugged slopes, arguably the most famous and widely read, Walden author Henry David Thoreau, came not to pen soaring verse, as his mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson enjoyed doing, nor solely to thrill at the view. Over the course of his relatively short life, Thoreau scaled Monadnock four or five times. Each time he’d train to Cheshire County, New Hampshire from his native Concord, Massachusetts wearing hobnailed boots and carrying plum cake and salt beef, his preferred camp rations. He detailed these expeditions in his journals. From them we know that Thoreau certainly admired Monadnock’s views. Yet what excited him even more than the summit were the summit’s berries: blueberries and huckleberries, and even the rare mountain cranberry. On Monadnock the sun-kissed treats thronged in easy abundance. “Nature heaps the table with berries for six weeks or more,” Thoreau wrote, a profusion “wholesome, bountiful, and free.” As they presented “real ambrosia” for anyone with enough energy to reap, Thoreau found it absurd that so few people stirred to the task.

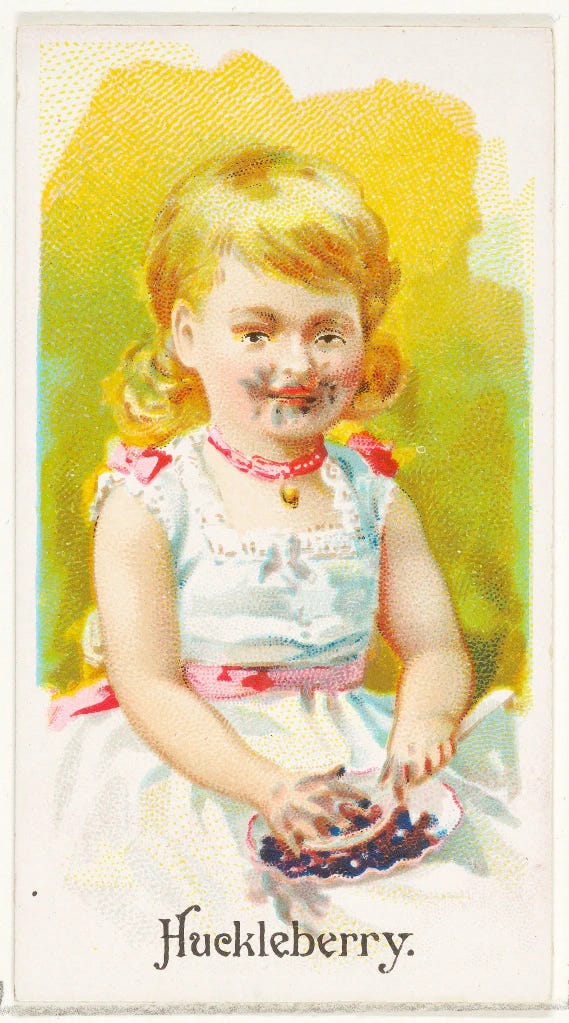

Thoreau himself found the task undeniably stirring. For Monadnock’s sweet plenty he cultivated truly discriminating tastes. He noted the differences in flavor among all the mountain’s berries, as well as differences within kinds. The huckleberry, for example, he deemed “palatable” and varying subtly in flavor according to conditions. These variations owed to the flavor’s being “slightly modified by soil and climate.” Huckleberries had a terroir. Pear-shaped huckleberries were sweet. Another sweet variety grew in swamps on bushes tall and slender and had skins stippled with resinous dots. And there was one variety of huckleberry so particular that it could be found in only three or four places in Concord. This variety was as sweet as it was rare — so sweet and rare in fact that Concord locals found it a suitable substitute for money. Thoreau, however, stood as an exception. A farmer once paid him in this medium of exchange, much to his dismay. “I shall beware of red huckleberry gifts in the future,” he vowed.

Thoreau esteemed wild huckleberries, if perhaps not as a wage. But he cherished mountain cranberries. “Perhaps the prettiest berry” he wrote in his journal after encountering several bushes on a trip up Monadnock in early August 1860, “certainly the most novel and interesting to me.” To Thoreau’s delight, they could be found on the mountain in decent numbers. On the low southern spur, he came across a patch nestled between the rocks among mosses and lichens. The plants rose scarcely one inch above the ground, yet he had no trouble spotting them. Their vines, covered in thick, glossy leaves, grew an inch-and-a-half in length. The red-cheeked berries clustered two or three together and equaled huckleberries in size. He eagerly dabbed here and there with his fingers pressed together, a technique he judged best for collecting mountain cranberries, until he had gathered a pint.

Thoreau ate the small harvest for breakfast the next morning. He stewed them over a fire, and thought they were the best fruit on Monadnock, despite being somewhat underripe and bitter. Indeed, he welcomed this sharpness. “It is such an acid as the camper-out craves,” he noted in his characteristically uncomplaining way. (His companion on this foray felt differently. George Emerson, cousin of Ralph Waldo, called the breakfast “austere,” and considered the mountain cranberry inferior to its common cousin of the lowland bogs in and around Concord.)

No more mindful or scrupulous a berry hunter was there than Thoreau. In his writings he not only kept extensive notes on his foraging; he also acknowledged his debt to those for whom the land and its bounty was their long heritage. In a piece entitled “Black Huckleberry,” Thoreau discusses how it was the indigenous peoples of New England who knew best how to collect and prepare wild berries. It was they who showed explorers and colonizers how to make the most of their nutrition and flavor. They sometimes added dried raspberries and blueberries to a bread made of pounded corn and boiled and mashed beans. They also dried them like prunes, reduced them to confits, mixed them in gruels, and baked them into loaves. And they made Sautauthig, the basis for which were berries that had been dried and pounded into meal. Thoreau mentions the regard in which Sautauthig was held, being to the native people “as sweet … as plum or spice cake is to the English.”

What berries the indigenous people did not eat fresh, they dried. Quoting American botanist John Bartram, Thoreau writes how women would set “four sticks in the ground,” each stick standing “about three or four feet high.” The women then laid “others across” and the resulting lattice served as a surface for saw-wort fronds. Thus was prepared a bed for berries, which the women spread “as malt is spread on the hair cloth over the kiln.” Under the berries the women kindled “a smoke fire." Once the berries were sufficiently dry, they were mixed into fresh maize bread baked in oblong loaves, which were so packed with huckleberries that they lay “as close in it as the raisins in a plum pudding.”

Thoreau took inspiration from these simple recipes. He too liked foods unadorned by spices and exotic ingredients, and he allowed himself only small portions. This was largely because he abhorred gluttony. To his mind, it was a vice that pushed out waistlines, certainly. Yet it also pushed out the borders of the nation. And Thoreau had no patience for the expansion of either. Such expansion meant to him nothing but rampant land speculation and waste, extermination of native people, and eventual degeneration of the entire country. “The gross feeder is a man in the larva state,” he wrote, “and there are whole nations in that condition, nations without fancy or imagination, whose vast abdomens betray them.” Thoreau believed that individuals sinned against nature when they overate, and that they compounded the sin when they ate food imported from outside their local environment. Thoreau was, in other words, a locavore, avant la lettre.

It’s a rare person who can commit to eating locally. The practice means long spates of dreary meals as foods go out of season. Present-day New Englanders, for example, would have to exchange the delights of oranges and strawberries in February for cabbages and dried apples. But the global trade that brings us such fruits also comes with trade-offs — and some bitterer than an underripe mountain cranberry, at that. A simpler, local, and more sustainable way of life no longer seems so humdrum. How convenient, then, that it’s nearly huckleberry season.

Thoreau recommends that foragers in New England look for berries beginning in the second or third week of July. By the first week of August, they’ll be at the peak of the season. What better way, then, to observe the occasion than by grabbing your pail to fill with huckleberries you’ve picked yourself. And what better way to enjoy your handpicked huckleberries than by baking them in a pie. The following simple recipe from Fruit Recipes: A Manual of the Food Value of Fruits and Nine Hundred Different Ways of Using Them (1907) will help you bake one to tempt even Thoreau to overindulgence. And don’t worry. If you need to work off the calories, the summit of Mt. Monadnock awaits you.

Whortleberry or Huckleberry Pie

Line the sides of baking dish or pan with paste and fill centre with the berries, sprinkling with sugar, adding a lump of butter and a tablespoon each of flour and water. Flavor with lemon or cranberry juice. Cover with crust or lattice strips and bake.